About Our Historic Amish Country Inn

From Pequea Valley's Early Settlers to a Modern Legacy of Hospitality

Early settlers...

Eastern Lancaster County, Pennsylvania is famed for the Pequea Valley, named after the meandering Pequea Creek. This creek encircles the Osceola Mill House Bed & Breakfast on three sides before joining the Susquehanna River near Holtwood. The land's first inhabitants were the Conestoga Tribe, known for their peaceful nature and early adoption of Christianity through trade with European settlers. The valley was included in the land granted to William Penn by King Charles II on March 4, 1681. Seeking religious freedom, European settlers, including the Huguenots in Paradise and Swiss-German Mennonite and Amish, rapidly populated the new colony. William Penn, upon receiving the charter, expressed his belief that this land, granted amidst many difficulties, would be blessed by God and become the seed of a nation.

1740s-50s

George MacKerel and his wife Agnes were the initial proprietors of 120 acres south of Pequea Creek, acquiring it from John, Thomas, and Richard Penn, sons of William Penn, on July 14, 1741. The property changed hands twice in fifteen years before Samuel Patterson bought it on June 8, 1756. Simultaneously, Patterson obtained water rights from John Huston, who owned adjacent land. Patterson intended to construct a dam to form a millpond, the remnants of which are visible near the house. In 1756, he erected the original grist mill nearby.

Regrettably, Samuel Patterson passed away shortly after the mill's completion. In 1758, executors of Patterson's will, sold the land, mill, water rights, and buildings to Jacob Ludwig and his wife Elizabeth.

1760s

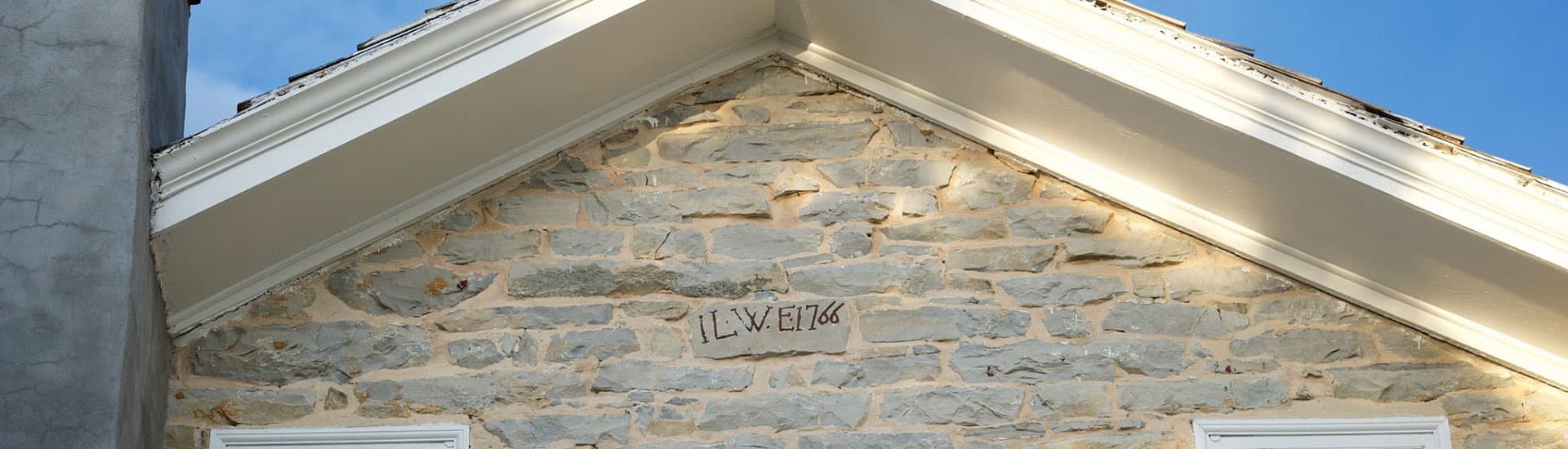

Jacob and Elizabeth,constructed the "Mill House Mansion" as their family residence. Stepping carefully onto Osceola Mill Road and gazing up at the peak of the west-facing wall reveals a date stone inscribed with "JL.W.E.1766," signifying "Jacob Ludwig and his wife Elizabeth in 1766." The mansion, crafted from locally-sourced limestone, showcases the elegant Georgian style. The Gathering Room, once their kitchen or great room, features a walk-in hearth and baking ovens. The Living Room and Dining Room, with their intricate mantels and woodwork, are believed to be original. According to an unverified legend, upon completing his mansion and relocating his family there, Jacob was approached by the local Church Elders. They suggested that the house was excessively opulent for a devout Mennonite family and advised him to demolish it and rebuild. Thankfully, he is said to have refused and chose to leave the Church instead.

1780s-90s

The Ludwigs had three children: Jacob, Catherine, and Elizabeth, who grew up in this family home. On May 21, 1783, Jacob and Elizabeth Ludwig transferred the property to Catherine and her spouse, George Eckert. It is documented that George Eckert expanded his land around the creek and the milling operations. From 1783 to 1796, assessment records indicate George Eckert's assets included a gristmill, sawmills, a forge, multiple horses, cattle, and a female servant. Their offspring, George Eckert Jr., is recognized in local annals as an industrial magnate and a man of considerable wealth, who leveraged his inherited land and, crucially, the water rights, to augment his fortune and status.

1800s

Over time, the property was subdivided, yet the majority remained within the Eckert family for generations until it was sold to Israel and Nancy Rohrer on April 1, 1868. The sale included 31 acres, a grist mill, sawmill, plaster mill, a two-story stone house, stone barn, two tenant houses, two stables, and water rights. Regrettably, this era was economically challenging for Pennsylvania, with much of its mining and milling industry relocating West, causing local businesses to suffer. In 1874, the Rohrer family faced foreclosure and lost the property in a public auction to David Landis for $17,500. Intriguingly, Landis then sold the property to Martin Rohrer, possibly a relative, just four days later.

1900s till today...

The mill and property never recaptured the prosperity it had under the Ludwig and Eckert family. Over the subsequent century, the property changed hands multiple times. In the mid 1960s, the Mill House was home to local artist Dolores Hackenberger. She and her husband raised their family in the home, before dividing and selling the mill, the foreman's house across the road, and the Mill House Mansion separately in the early 1980s. The mill was purchased by Charles Shoemaker and restored into a private home; he and his wife, Mary remain the owners. Dr. Edward Frost, a dentist from New York City, and his wife acquired the foreman's house, using it as their country retreat until selling it to a local Amish neighbor in 2013. The Mill House Mansion, along with about an acre of land, was transformed into a Bed and Breakfast with various owners since then taking great care to preserve and maintain the property.

How did the Mill House Mansion get such an unusual name?

The original name of the Mill was Springwell Forge, named by George Eckert. The name was changed to The Osceola Mill by Martin Rohrer in 1875. There is no documentation as to his reason for the change, but there is speculation. Chief Osceola was a Seminole with a prominent reputation for his leadership and resistance to the US government’s takeover of Native American land. After his imprisonment in 1837, there was an uproar over the deceitful method of his capture, and news traveled quickly to PA, where support of oppressed people of the South, including the Underground Railroad, has a long and prominent history. It is not hard to imagine Rohrer’s inclination to honor the legendary Chief.